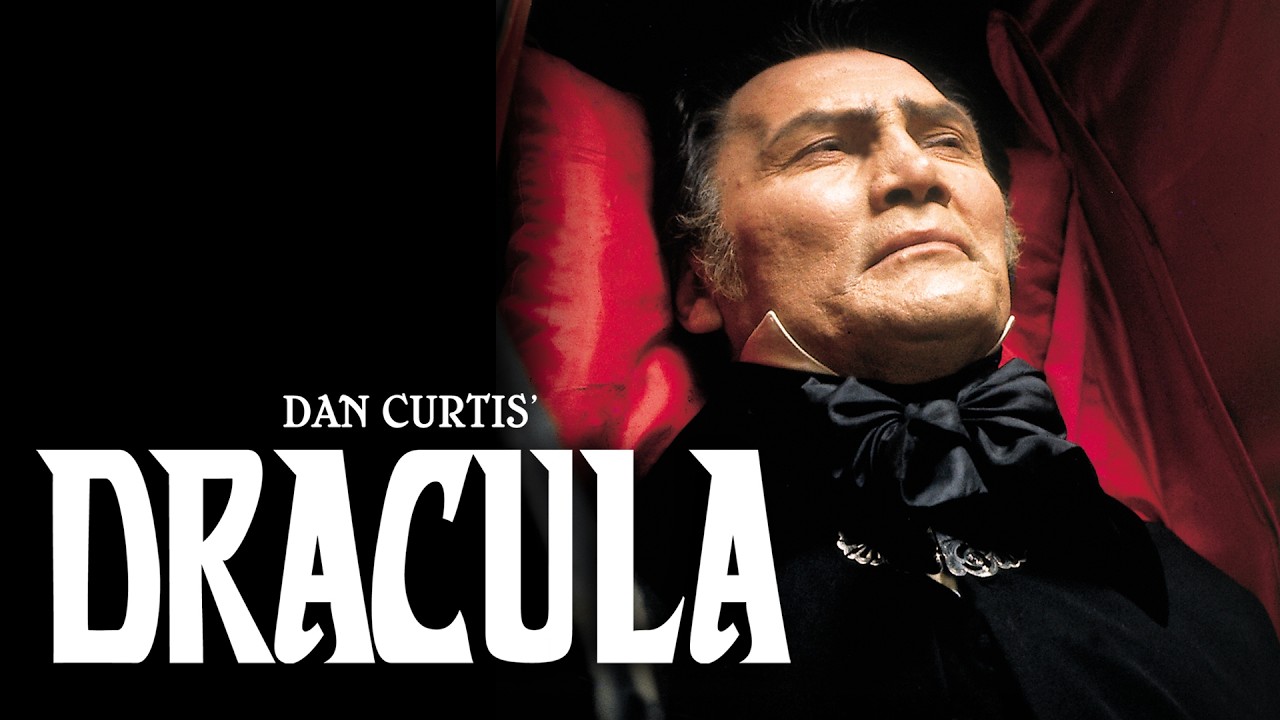

In 1973, Dan Curtis (1927-2006), the creator of Dark Shadows, traveled to England and Yugoslavia to direct his acclaimed version of Dracula, based on Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel. The film, sometimes known as Bram Stoker’s Dracula or Dan Curtis’ Dracula, aired on CBS-TV on Friday February 8, 1974, after the fifth episode of Dirty Sally and the first episode of Good Times.

Dracula was the fourth of six collaborations between Curtis and author Richard Matheson (1926-2013), who had written about vampires in such 1950s stories and novels as “Blood Son,” “The Funeral” and I Am Legend. Matheson’s 1959 story “No Such Thing as a Vampire” had been filmed for the Friday April 19, 1968, premiere episode of BBC-TV’s Late-Night Horror—one of the very first BBC productions filmed in color—before Dan Curtis remade it in 1973.

Matheson recalled that his and Curtis’ Dracula (whose running time is 1 hour, 38 minutes) aired in a two-hour timeslot. He added, “It turned out quite well, I thought, but it was even better at three hours originally shot. I wrote a script for three hours and Dan shot a three-hour version, but the network would give us only two hours. So Dan had to edit it down. I would have loved to have seen it at three hours. It was the first one that tried to follow the book and the first one to use the Vlad the Impaler material. To this day, I think we came the closest.”

What Matheson includes in his adaptation is an accurate reproduction of Stoker’s novel, especially the book’s first four chapters (relating Jonathan Harker’s stay at Castle Dracula), as well as the shipwreck of the Demeter (chapter 7), Dracula’s release of a wolf from the zoo (chapter 11), Mina’s drinking of Dracula’s blood from an open wound (chapter 21) and Van Helsing’s hypnosis of Mina (chapter 23). However, Matheson omits the characters of Quincey Morris (often absent from film adaptations), Dr. John Seward and the mad R.M. Renfield. The adaptation works without the Seward/Renfield subplot as it focuses fully on Jonathan Harker (Murray Brown), Mina Murray (Penelope Horner), Arthur Holmwood (Simon Ward), Lucy Westenra (Fiona Lewis), Mrs. Westenra (Pamela Brown), Dr. Abraham Van Helsing (Nigel Davenport) and Count Dracula (Jack Palance).

Dan Curtis’ Dracula makes two significant changes, one of which makes this adaptation so distinctive and influential. In the novel, Jonathan’s opening storyline leaves him (at the end of chapter 4) a prisoner of Castle Dracula and at the mercy of Dracula’s three vampire brides (played in the movie by Sarah Douglas, Barbara Lindley and Virginia Wetherell). Four chapters later, Mina receives word that Jonathan is in a hospital in Budapest. Stoker never explains exactly how Harker managed to escape the castle. In Curtis’ version, Jonathan does not escape. When Arthur and Van Helsing arrive at Castle Dracula, they find that their friend has become a vampire (echoing Harker’s fate in 1958’s Horror of Dracula).

The more important change is the revisionist explanation of why Dracula comes to England in the first place. Stoker does not offer a reason until chapter 24 when Van Helsing assumes that Dracula is “leaving his own barren land—barren of peoples—and coming to a new land where life of man teems ‘til they are like the multitude of standing corn.” In other words, Dracula may as well relocate near the world’s largest city (London) in order to have an endless supply of victims. Curtis insisted, “Richard Matheson, who’s a wonderful writer, and I adapted the Bram Stoker novel and brought to it something that wasn’t in it. I ripped myself off. I took the Dark Shadows love story and put it in our Dracula because in the novel, Dracula leaves Transylvania and goes to England for no reason at all. Stoker says he’s sucked virtually everybody dry down there, and he had to find new blood. We didn’t do that. I always felt that was ridiculous, so we came up with the central love story to Dracula that never existed in the novel but that has since, I might add, been copied by other Draculas, the most recent one, for instance.’

Curtis referred to Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). However, the animated adventures The Batman vs. Dracula (2005) and Highlander: The Search for Vengeance (2006) also fit this description. So do Fred Olen Ray’s vampire serial The Lair (2007-2009) and the CW series The Vampire Diaries (2009-2017). More recently, Luc Besson’s 2025 adaptation of Dracula fully embraces the romantic angle; the film’s full name is Dracula: A Love Tale, and there is even a music box as in Matheson and Curtis’s Dracula.

Curtis added, “In our movie, he [Dracula] saw a picture of a girl [Lucy] in the newspaper, and we established that she was the reincarnation of this woman he was in love with in the 1400s. She’s in England, and he goes to England to get her back. It’s a little Dark Shadowy, but it worked. It was perfect. That’s why our Dracula was as good as it was. It brought to the monster a degree of sympathy. Instead of making him just this marauding vampire, he was a haunted figure. You really cared about him even though you were terrified of him. Jack [Palance] is extraordinary. Jack is the best Dracula there ever was. He was the most frightening Dracula that ever put on that cape.”

The Los Angeles Times agreed. “This two-hour version of the classic horror story made for television by Dan Curtis and offered tonight on CBS would chill the bones of a plaster saint. It’s as flesh-crawling an experience as you’ve ever had.” The Times proclaimed, “If the late [Bela] Lugosi was the definitive Count Dracula, it’s no longer true. It’s now Jack Palance.”

In a 2000 DVD featurette, Palance (1919-2006) mused that Count Dracula was “the only character I ever played that frightened me even in the doing of it. But I never thought of the character as evil. He was someone who was trapped in a situation.” Palance added that with Curtis at the helm of the movie, “I knew it would be done very well and with great authenticity.” Donald F. Glut, author of The Dracula Book (Scarecrow, 1975), agreed: “The film surely ranks with the best movie adaptations of Stoker’s Dracula, and it firmly establishes director Curtis and actor Palance among the genre’s upper echelon.”

That newfound authenticity is the other hallmark of Curtis’ Dracula—and the other ingredient that Coppola’s 1992 blockbuster and Bresson’s 2025 Love Tale appropriated from their 1974 predecessor. Except for one line in Mehmet Muktar’s 1953 Turkish film Drakula Istanbul’da (Dracula in Istanbul)—“The locals believe that I, like my ancestor Voyvodo Drakula, am ruthless”—Curtis’ Dracula is the first Dracula film to make an explicit connection between Count Dracula and the real-life Vlad the Impaler of the 15th century. Matheson’s screenplay reflects the scholarship of the time in Raymond McNally and Radu Florescu’s In Search of Dracula (Houghton-Mifflin, 1972) and Dracula: A Biography of Vlad the Impaler, 1431-1476 (its 1973 follow-up).

Twenty-first-century film audiences take for granted that the Dracula character is based on the real-life story of a ruthless warrior, but at the time of Curtis’ Dracula, such an idea was just coming into the public consciousness. Vlad Dracula, also known as Vlad Tepes, was born in Sighiroara (a.k.a. Schassburg), a village in Transylvania, in late 1430 or early 1431. His father, Vlad Dracul, had been prince of Wallachia and a member of the Order of the Dragon, a Christian brotherhood founded by King Sigismund I of Hungary in 1418 and dedicated to fighting the Turkish people. “Drac” is a Romanian word meaning “dragon” or “devil,” and Vlad Dracul’s son was called Dracula, or “son of the dragon” or “son of the devil.” In later life, Vlad Dracula also was called “Tepes,” which means “impaler,” because of his penchant for skewering as many of his enemies as possible. Vlad had many of them, for he spent his life attacking the Turkish people and fighting to acquire and keep the throne of Wallachia. After putting to death 40,000 of his enemies (four times more than Ivan the Terrible), Vlad fell to an assassin in December 1476 or early January 1477.

Some evidence of Count Dracula’s having been patterned after Vlad Tepes exists in Bram Stoker’s novel. In chapter 3, Harker notes that Dracula sounds “like a king speaking” when the Count talks knowingly of his family’s “guarding of the frontier of Turkey-land.” Dracula declares:

“Who was it but one of my own race who as Voivode crossed the Danube and beat the Turk on his own ground? This was a Dracula indeed! [. . .] Was it not this Dracula, indeed, who inspired that other of his race who in a later age again and again brought his forces over the great river into Turkey-land; who, when he was beaten back, came again, and again and again, though he had to come alone from the bloody field where his troops were being slaughtered, since he knew that he alone could ultimately triumph! They said that he thought only of himself. Bah! What good are peasants without a leader? Where ends the war without a brain and heart to conduct it? Again, when, after the battle of Mohacs, we threw off the Hungarian yoke, we of the Dracula brood were amongst their leaders, for our spirit would not brook that we were not free.”

Later, in chapter 18, as Van Helsing is explaining the rules of vampirism to Mina and the others, he reports his own findings about Dracula’s origins: “Thus, when we find the habitation of this man-that-was, we can confine him to his coffin and destroy him, if we obey what we know. But he is clever. I have asked my friend Arminius, of Buda-Peth University, to make this record; and, from all the means that are, he tells me of what he has been. He must, indeed, have been that Voivode Dracula who won his name against the Turk, over the great river on the very frontier of Turkey-land. If it be so, then he was no common man; for in that time, and for centuries after, he was spoken of as the cleverest and the most cunning, as well as the bravest of the sons of the ‘land beyond the forest.’ That mighty brain and that iron resolution went with him to his grave, and are even now arrayed against us. The Draculas were, says Arminius, a great and noble race, though now and again were scions who were held by their coevals to have had dealings with the Evil One. They learned his secrets at the Scholomance, amongst the mountains over Lake Hermanstadt, where the devil claims the tenth scholar as his due. In the records are such words as ‘stregoic’—witch, ‘ordog,’ and ‘pokol’—Satan and hell; and in one manuscript, this very Dracula is spoken of as ‘wampyr,’ which we all understand too well.”

Van Helsing’s “friend Arminius” is the real-life Hungarian historian Arminius Vambery, author of Hungary in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times (1886) and other books of history and travel. Bram Stoker met Vambery at the Beefsteak Room, behind the Lyceum Theatre, in 1890 when Stoker was 43 and Vambery was 58. (The restaurant is mentioned in Masterpiece Theatre’s 2007 reimagining of Dracula.) At the time that he met Vambery, Stoker had begun to write Dracula, and it is possible that Vambery told Stoker stories of Vlad the Impaler—stories that the leading Hungarian scholar doubtless knew even though he himself never wrote about Vlad Tepes in any of his own books. “The land beyond the forest” refers both to the literal translation of “transylvania” and to Emily Gerard Laszowska’s 1888 book, The Land Beyond the Forest: Facts, Figures, and Fairies from Transylvania, which Stoker is known to have read when he was gathering information about the region.

The Scholomance is a legendary school of occult sciences and necromancy—a kind of antediluvian Hogwarts—where Count Dracula studied and perhaps where he lost his soul to the powers of darkness and became a vampire. (Stoker offers no concrete explanation as to how Dracula became undead centuries ago, but he strongly hints that sorcery was involved.) Students at the Scholomance are taught by a dragon and/or the devil how to affect weather and how to transform themselves into animals. Dracula’s name suggests both “dragon” and “devil.”

In Curtis and Matheson’s groundbreaking film, Count Dracula is seen as a medieval warrior prince in two brief flashbacks and in an enormous painting. The nameplate below the painting of the kingly soldier on horseback even names him as “Vlad Tepes, Prince of Wallachia, 1475.” In one scene, Dracula refers to himself as “me, who commanded armies hundreds of years before you were born.” Indeed, in the summer of 1475, Vlad had regained the throne and then led armies into Serbia and Turkey.

Finally, after Van Helsing and Arthur Holmwood succeed in destroying the vampire, an epigraph in red letters on the screen proclaims, In the 15th Century, in the area of Hungary known as Transylvania, there lived a nobleman so fierce in battle that his troops gave him the name Dracula, which means devil. Soldier, statesman, alchemist and warrior, so powerful a man was he that it was claimed he succeeded in overcoming even physical death. To this day, it has yet to be disproven. Richard Matheson’s words echo Dr. Seward’s diary entry in chapter 23 of Stoker’s novel: He was in life a most wonderful man. Soldier, statesman, and alchemist—which latter was the highest development of the science-knowledge of his time. He had a mighty brain, a learning beyond compare, and a heart that knew no fear and no remorse. He dared even to attend the Scholomance, and there was no branch of knowledge of his time that he did not essay. Well, in him, the brain powers survived the physical death.

The film takes place in Bistriz, Hungary, in May 1897; “five weeks later” near Whitby, England; and finally, back in Hungary. The scenes of Jonathan Harker’s captivity in Castle Dracula are atmospheric and frightening. Count Dracula and his vampire brides show a feral side that is quite unnerving. The scares continue in England as a wolf attacks Arthur Holmwood and Dracula vampirizes Lucy Westenra, who seems to be the reincarnation of Dracula’s lost love. The scenes of Lucy’s macabre death and rainy funeral are reminiscent of the corresponding scenes with Carolyn Stoddard in Curtis’ House of Dark Shadows (1970).

One of the most chilling moments in Dracula is Arthur’s sighting of Lucy, now a vampire, plaintively rapping on the window and begging Arthur to let her come in. Another scary highlight is the mayhem that the superhuman Count Dracula causes at the George Hotel where Mina Murray and Mrs. Westenra are staying.

One of the most shocking moments (especially for 1974-era television) is Dracula’s opening a wound on his torso and forcing Mina to drink his blood while Arthur Holmwood and Dr. Abraham Van Helsing stand by helplessly. The overseas theatrical cut of Dracula (for England, France, Japan, South America, et al.) is even gorier. Blood gushes from the mouths of Lucy and one of the vampire brides when they are staked, and blood bursts from Dracula’s mouth when he is impaled in the sunlight.

Curtis’ film editor was Richard A. Harris (born 1934), who also edited Matheson and Curtis’ Scream of the Wolf (1974) and three other Dan Curtis productions before he edited two Bad News Bears movies, two Fletch movies and three Arnold Schwarzenegger movies. Harris won the Academy Award for editing James Cameron’s Titanic (1997).

For Dan Curtis’ Dracula, composer Robert Cobert (1924-2020) wrote a majestic, martial fanfare for the former warrior prince, as well as a dynamic main-title theme in the key of C minor. Cobert explained, “I wrote a love theme for Dracula that came from a music box. [. . .] I was the first composer to write a love theme for Dracula because Dan’s Dracula had a love story in it. [. . .] I wrote something modal, with a Romanian accent, the kind of music box that he might have had.” By “modal,” Cobert meant something evocative of medieval church music.

“In a number of movies we did,” Cobert added, “I had a music box somewhere.” Indeed, House of Dark Shadows (1970), Come Die with Me (1974) and Burnt Offerings (1976) feature music-box themes, continuing a practice begun on the 1966-1971 Dark Shadows television series with Josette’s Music Box. “When I wrote the Dracula music-box theme, I played it for Dan, and at first he didn’t like it. He said, ‘It sounds sad.’ I said, ‘Of course it sounds sad. He’s Dracula. He’s sad!’ It was a Hungarian music box rather than a Mozartian music box. Then, that music-box theme becomes the love theme, with full orchestra, and it morphs into danger halfway through.”

Cobert was given three weeks to write the music for Dracula. “That was a longer time than usual,” he remembered. “I usually got two weeks to write a movie score. I wrote the Dracula music at my beach house in the Hamptons. Writing it was a happy, rewarding experience. Whenever I did a movie with Dan, he and I sat down with a music editor, who took notes, and Dan showed me the movie. Then, we decided where the music should go. He’d say, ‘We need something here,’ and I’d say, ‘We need something there,’ and we worked it out. Dan said, ‘You gotta write something big for the death of Dracula,’ so I did. I ended with the theme for Dracula as the warrior and then the music box.”

The music, recorded by a 40-piece orchestra in London, was only one of many elements that made Curtis’ Dracula an important addition to the nearly 200 film adaptations of Bram Stoker’s novel since 1920. Of all of the actors who have portrayed the vampire, Jack Palance brought unique ferocity to the role and pioneered Dracula’s cinematic portrayal as Vlad the Impaler (as he is seen later in the Coppola and Besson films). Radu Florescu and Raymond McNally noted Palance’s portrayal of Vlad Dracula and declared, “The best scene is where Dracula, upon finding that his long-lost love has been destroyed, groans like a wild animal as he smashes the funeral uns. In the final scene, Dracula is killed by a huge lance as the sun is coming up.”

Dr. J. Gordon Melton, author of The Vampire Book: The Encyclopedia of the Undead (Visible Ink, 1994), added, “Knowledge of the historical Dracula has had a marked influence on both Dracula movies and fiction. Two of the more important Dracula movies, Dracula (1974), starring Jack Palance, and Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a recent [1992] production directed by Francis Ford Coppola, attempted to integrate the historical research on Vlad the Impaler into the story and used it as a rationale to make Dracula’s actions more comprehensible.”

Dan Curtis confidently insisted that his, Matheson’s, and Palance’s film “is the best Dracula that was ever made! It was very erotic, without showing a hell of a lot, and very scary and done with a lot of classic style. We had a wonderful director of photography, Ossie Morris, and we shot it in England and Yugoslavia. It was a really good production.” Variety called it “a tribute to Palance, Curtis, and Matheson that it comes off as logically as it does.” Variety continued, “Curtis and Matheson, ignoring previous flourishes made out of Bram Stoker’s Victorian novel, approach the tale with a fresh, realistic fashion, designed to chill. With Jack Palance turning in one of the finest performances of his career as the bloodthirsty nobleman, Matheson has brought out the essential elements of the story. [. . .] Stoker, Sir Henry Irving’s business manager as well as a novelist, would be delighted.”

Dracula benefits from beautiful cinematography by Oswald “Ossie” Morris (1915-2014), who recently had won the Academy Award for his cinematography of Norman Jewison’s Fiddler on the Roof (1971). Morris photographed notable movies from Moulin Rouge (1952) to Lolita (1962) to Sleuth (1972) to The Dark Crystal (1982), and he imbued Dracula with gorgeous shots of the Yugoslavian countryside, high-angle shots of running wolves, and Curtis’ trademark low-angle shots of the actors. Oswald Morris photographed Dracula around the time that he shot The Mackintosh Man (1973), The Odessa File (1973), and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974), the James Bond movie that co-starred another one of the best movie Draculas, Christopher Lee.

CBS reran Dracula in prime time and late-night in the mid-1970s, and A&E and local TV stations showed it in the 1980s and 1990s. CBS re-re-aired it on Saturday November 28, 1992, in order to take advantage of the momentary upswing of interest in Dracula—especially Dracula as Vlad Tepes—because of the release of Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula on Friday November 13, 1992. Fans were delighted to see 1992 end with a Dan Curtis classic to complement the new production, Angie the Lieutenant (February 1) and Intruders: They Are Among Us (May 17 and 19). When Dracula was telecast on November 28, Dan Curtis was busy filming Me and the Kid (1993).

As excellent as Dracula is as a two-hour movie, it would have been even more epic as the three-hour film that Curtis and Matheson had envisioned. Sadly, almost all of the extra, unused footage for a three-hour Dracula was lost some time in the 1980s. The MPI Blu-ray of Dracula features the only remaining extra footage, “a few odd scraps” that Jim Pierson found “in a can of trailer outtakes” as Pierson was restoring the film for the Blu-ray release and a gala screening at the Vista Theatre in Los Angeles on Wednesday April 30, 2014. The scraps reveal nothing new: they are soundless shots of Jack Palance posing as Dracula, Arthur and Van Helsing protecting Lucy as she sleeps and Van Helsing hypnotizing Mina and staking Lucy and one of the brides.

Luckily, Matheson’s three-act “screen treatment” (plot synopsis) and 140-page script (dated 7 August 1972) do exist and were published in Mark Dawidziak’s 2006 Gauntlet Press book Bloodlines: Richard Matheson’s Dracula, I Am Legend, and Other Vampire Stories. Dawidziak dedicated the book “to Dan [Curtis] and Darren [McGavin], both legends.”

Matheson’s typewritten script is that of a nearly three-hour-long film that very closely resembles the finished two-hour movie—with a few significant exceptions. In the first scenes at Castle Dracula, Matheson’s script calls for Count Dracula to appear as an old man with his fingernails “cut to a point” as in Bram Stoker’s novel. It is only after biting Lucy that “Dracula now looks like a vigorous man in his forties.”

In the scene in which Dracula prevents his three wives from feeding on Jonathan, Dracula “has a moving sack in his hands.” The script calls for “a momentary glimpse of a half-dead little girl,” upon whom “the hideous trio” pounces. Next, the little girl’s parents are standing outside the castle and screaming for Dracula to give their child back to them. The vampire summons a pack of wolves to attack the parents,

Other elements that do not transfer from script to screen are several more shots of Dracula’s driving his carriage to and from the George Hotel, an image of the undead Lucy’s tempting Arthur by showing her breasts to him, and a glimpse of Lucy’s severed head. (Van Helsing does not cut off Lucy’s or any vampire’s head in the finished film.) In the scene in which Dracula bursts in to Mina and Mrs. Westenra’s hotel room, Matheson calls for Mrs. Westenra’s death at Dracula’s hands, but Curtis leaves her alive.

A major difference between the script and the film is that Matheson, like Stoker, allows Jonathan Harker to escape from Castle Dracula. Mina receives a letter from “the hospital of St. Joseph and St. Mary, its address in Buda-Peth. CAMERA MOVES DOWN on one of the lines in the handwritten letter. He has been under our care for nearly six weeks, suffering from a violent brain fever.”

When Mina arrives at the hospital in Budapest, Hungary, a nun takes her to the Mother Superior, who tells her that Jonathan has died. “Two days ago,” she informs Mina. “We sent another telegram, but, obviously, you’d left already.”

Mina sobs, begins to cry. The Mother Superior puts her hand on her shoulder. After a while, Mina looks up.

MINA

May I see him?

MOTHER SUPERIOR

I’m afraid that’s impossible.

MINA

Why?

MOTHER SUPERIOR

His…body was…disposed of.

MINA

Disposed of? What do you mean?

The Mother Superior swallows nervously, braces herself, then speaks again.

MOTHER SUPERIOR

It was burned.

CAMERA MOVES IN QUICKLY ON Mina’s stunned expression.

Other differences emerge at the end of the script when Arthur Holmwood and Abraham Van Helsing close in on the vampire at Castle Dracula. Matheson calls for the novel’s horde of rats, as well as Dracula’s gold coins that spill from his pockets after his impaled body begins “to atrophy as he dies.”

CAMERA APPROACHING his dead body as, like ancient dust, it starts to drizzle greyly to the floor, leaving his shirt and his coat suspended on the pike. As they begin to sag, gold coins start to drop from the pockets.

CAMERA down-tilts to the coins as they fall on the floor.

MOVING SHOT—CLOSE ON COIN as it rolls across the floor to Van Helsing and stops. His hand reaches INTO FRAME and picks it up,

CAMERA RISING TO REVEAL him gazing at the coin.

P.O.V. SHOT—GOLD COIN—CAMERA MOVES IN ON the ancient gold coin. On its face is the head of Dracula; beneath it, his name and the date in Roman numerals, 1410. Faint CROWD NOISES begin.

The script, as well as the movie, ends with the crowd noises, the shot of Dracula’s portrait and the “crawl title” in red letters. Matheson and Curtis’ film is largely faithful to Stoker’s novel, but the additions of Old Dracula, Jonathan’s escape (but not death yet), the rats, and the gold coins would have made the movie even more faithful.

What the typewritten script does not include is the creative input of director Dan Curtis. In Matheson’s script, there is no scene in which Harker, now a vampire, attacks Holmwood and Van Helsing; there is no music box; there are no flashbacks to the life (brief love scene) and death (brief deathbed scene) of Dracula’s long-lost love (Fiona Lewis); and there is no all-important moment (as in Horror of Dracula [1958] and several Dark Shadows episodes [1968 et al.]) when the vampire slayers flood the room with sunlight and stun the monster before they destroy him. Apparently, these scenes in the movie were devised by Dan Curtis (with input from Robert Cobert and Richard Matheson).

Mark Dawidziak’s aforementioned Bloodlines book published Matheson’s extremely detailed “screen treatment,” which reveals the plot of the three-hour-long script and film that might have been. The treatment, too, first describes Count Dracula as “a tall, old man, clean-shaven except for a long, white moustache, [and] dressed entirely in black.” After Dracula goes to England and begins feeding on Lucy, he is “a very different Dracula, no longer old but seemingly, incredibly, becoming young again.” Later, after several nights when Arthur and his godfather Van Helsing prevent Lucy from going to Dracula, “the infuriated vampire [is] starting to age again.”

According to Dawidziak, Matheson lamented the shortening of his and Curtis’ Dracula from three hours to two hours because (in Matheson’s words) “it needed that extra hour” to be the nearly complete and definitive Dracula adaptation that Matheson had envisioned. Dawidziak added, “Nowhere is this more evident than in the downward spiral experienced by the character of Jonathan Harker. In Matheson’s screen treatment, Jonathan is sent to Transylvania, where he is imprisoned by Dracula. He escapes from Castle Dracula and, as in the book, is reunited with his fiancée, Mina, in a Budapest hospital operated by nuns. Jonathan and Mina join Arthur and Van Helsing in the hunt for Dracula, a hunt that leads back to Castle Dracula. Fittingly, it is Jonathan who administers the death blow, thrusting a medieval pike through the vampire’s heart.”

“That’s all pretty much in keeping with Stoker’s novel. In the script written for a three-hour timeslot, though, Jonathan is killed off in Budapest. He manages to escape from Dracula’s castle, only to die before Mina can make it the hospital. Can things get any worse for poor Jonathan? Well, sure. He was played by Keanu Reeves in the [1992] Coppola version, and that was a fate worse than death. Curtis also had a nasty fate for him. In the director-producer’s final cut, Jonathan disappears from the story, only to rush out of the darkness at the end as a vampire lurking in Castle Dracula. He went from impaling Dracula to getting staked himself. He went from conquering hero revisiting Castle Dracula to never having escaped the Transylvanian fortress. Jonathan’s shocking reappearance definitely is a “made-you-jump” moment in the film, yet it hardly adheres to the kind of fidelity that Matheson advised in the screen treatment. Still, even if the two-hour version of [Dan Curtis’s] Dracula (actually 100 minutes plus commercials) falls short of being definitive, it does meet two of the essential goals stated by Matheson in the screen treatment. “What cannot be eliminated—must not be eliminated—is the overwhelming sense of credible, intimate horror which the book transmits to its readers,” he maintained. Curtis and his team certainly captured that. The other goal stated by Matheson and achieved by this Dracula is that it convinces the viewer that “an attempt is being made to present a literate, intelligent, adult version of a marvelously terrifying story.” From screen treatment to screenplay to screen, this attempt distinguishes the Matheson take on Dracula.”

If Dan Curtis had had that extra hour (for the Harker story arc, which included a hypnosis scene), a bigger budget (for the rats, the coins, Old Dracula and other touches), and more freedom (for the horrifying moment with the little girl and her parents), Dan Curtis’ Dracula (TV-1974) would have been the definitive version of the oft-filmed story. As it is, it ranks with Gerald Savory and Philip Savile’s Count Dracula (TV-1977) and one or two other films as one of the most nearly definitive adaptations of Dracula. Like Curtis’ mostly faithful versions of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and The Picture of Dorian Gray, Matheson and Curtis’ Dracula is a major touchstone in horror television.

According to Richard Matheson, “I think it came as close as you could with just two hours, but there was quite a bit missing. I would have loved to have seen it at three hours. [. . .] That would have been dandy. Then, we could have really done it to a fare-thee-well. But even at the shorter time, it still came off very well. [. . .] It was the first one that tried to follow the book and the first one to use the Vlad the Impaler material. To this day, I think we came the closest.”

Dan Curtis certainly agreed. Dracula (1974) and Burnt Offerings (1976) are two of his greatest achievements in horror. In the early 2000s, Curtis reflected on his rich legacy of television and movie horror. He revealed, “Horror stories are the most difficult types of things to do because you need imagination and humor, and you can never make a mistake. The first screw-up, you lose all credibility, and you’re dead with the audience. Most people say, ‘Well, it’s a ghost, so we can do whatever we want with it.’ They’re the people who are dead before they start. A logic lapse or the wrong kind of laugh can sink you. Every single word is a deathtrap. That’s the worst part of it. Every single line in a horror picture becomes dangerous. A simple “hello” at the wrong place can bring an unwanted laugh. You don’t want any unwanted laughs. You want chuckles in the right places. You want people smiling with you when you do certain things. So if you can do these kinds of pictures, you can do anything. Most people think just the opposite—that if you can do these kinds of pictures, you can’t do anything else. Well, I’ve proven them wrong.”

Dracula (CBS, 8 February 1974). Producer: Dan Curtis. Associate producer: Robert Singer. Director: Dan Curtis. First assistant director: Derek Kavanaugh. Teleplay: Richard Matheson (based on the novel by Bram Stoker). Music: Robert Cobert. Director of photography: Oswald Morris. Production designer: Trevor Williams. Makeup: Paul Rabiger. Costumer: Ruth Myers.

Cast: Jack Palance (Count Dracula), Nigel Davenport (Dr. Abraham Van Helsing), Murray Brown (Jonathan Harker), Penelope Horner (Mina Murray), Simon Ward (Arthur Holmwood), Fiona Lewis (Lucy Westenra), Pamela Brown (Mrs. Westenra), Reg Lye (zookeeper), Sarah Douglas (bride), Barbara Lindley (bride), Virginia Wetherell Bates (bride). 98 minutes. Available on VHS, DVD, and BRD (Blu-ray disc).

See Jeff Thompson’s Rondo Award-nominated book Nights of Dan Curtis: The Television Epics of the Dark Shadows Auteur (Ideas, 2020) for more information about Dracula, including endnotes and photographs.

The award-winning producer-director Dan Curtis could do it all—and did. For tele-vision, Curtis created the Gothic serial Dark Shadows and made horror movies (The Night Strangler), crime dramas (The Kansas City Massacre), love stories (The Love Letter), family dramas (The Long Days of Summer), war stories (The Winds of War), and a Western (The Last Ride of the Dalton Gang).

***

All three of Jeff Thompson’s books about Dan Curtis present 75 to 115 “incredible photographs and excellent detail” (Canyon News) about Dark Shadows and all four dozen of Curtis’s productions, from Challenge Golf (1963) to Our Fathers (2005), as well as details about planned productions that never were, such asThe Last of the Crazy People, Diary of a Gunfighter, and Wuthering Heights.

The Television Horrors of Dan Curtis provides additional focus on Curtis’s horror productions, including Trilogy of Terror and Burnt Offerings. House of Dan Curtis takes a closer look at Curtis’s mysteries and crime dramas, including Come Die with Me and Melvin Purvis, G-Man. Nights of Dan Curtis specializes in Curtis’s epic productions, from Dracula to The Winds of War to War and Remembrance to Intruders: They Are Among Us and more.

These three books (two of them Rondo Award-nominated) also feature information about recent Dark Shadows projects and media, as well as forewords and afterwords by Ansel Faraj (Loon Lake), Jim Pierson (My Music), James Storm (Dark Shadows), and Larry Wilcox (CHiPs). They are “highly recommended” (Examiner.com and Midwest Book Review) and cover “every-thing the man produced” (Video Scope). Dr. Jeff Thompson, a lifelong teacher, writer, and col-lector, provides comprehensive research, unusual anecdotes, and performers’ comments about Dan Curtis and his unforgettable productions, as well as the words of Curtis himself.

The books are available from Amazon, McFarlandBooks.com, & IdeasIntoBooks.net.

Tags: Dan Curtis