Harry Turtledove has spent most of his career reimagining history—altering outcomes, bending timelines, and asking how the world might look if one crucial detail changed. With his City of Shadows novels, he turns that instinct inward, away from grand geopolitical shifts and toward the streets of postwar Los Angeles, imagining a city where the supernatural doesn’t lurk in secret. It lives openly among the rest of us, woven into the same corruption, compromise, and survival instincts that have always defined noir.

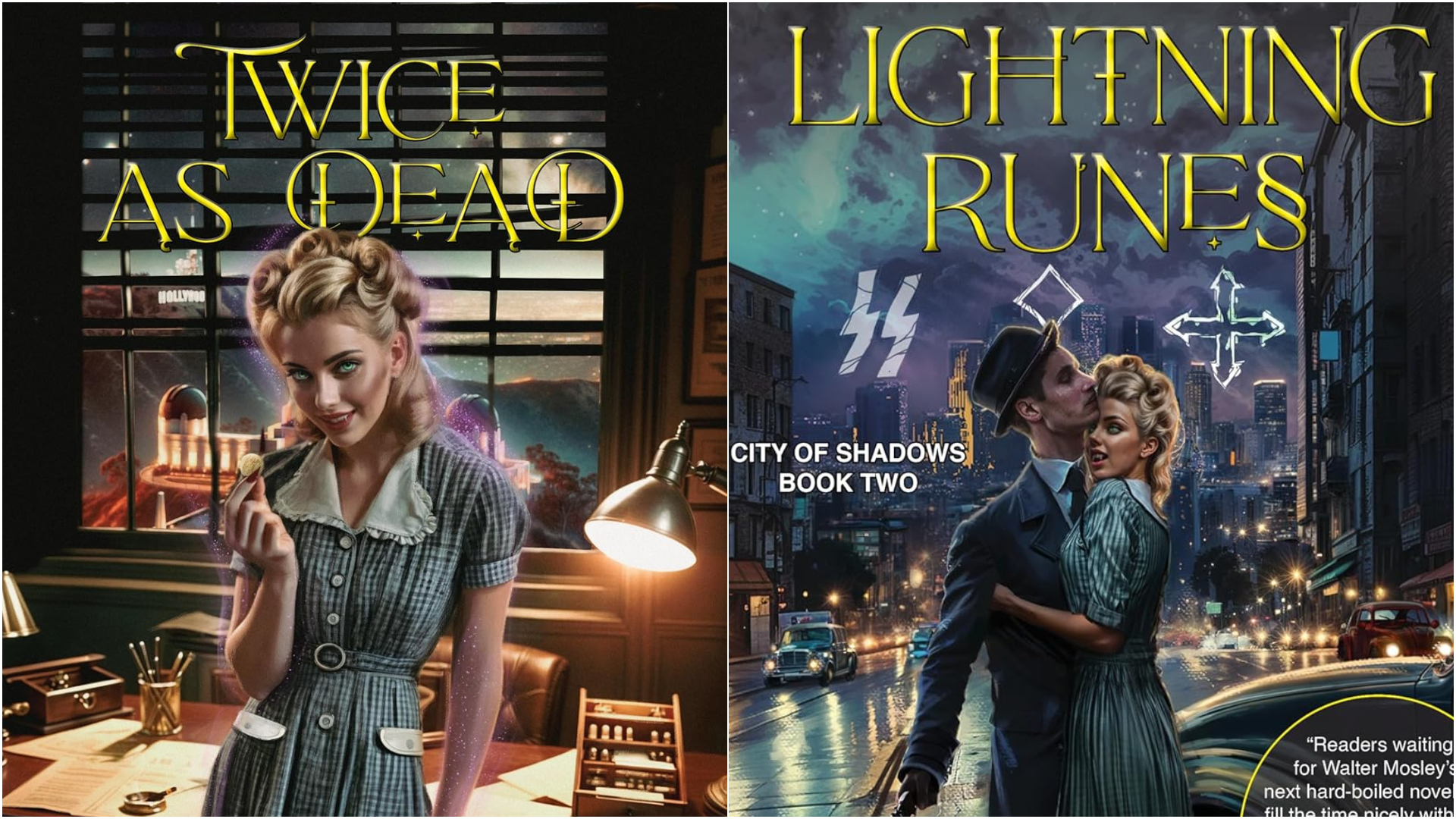

The first two books in the series, Twice as Dead and Lightning Runes, take the familiar rhythms of hardboiled detective fiction and layer them with vampires, magic, and ghosts—not as spectacle, but as part of the city’s everyday machinery. The result isn’t a genre mash-up chasing novelty. It’s a noir story that simply happens to acknowledge that monsters exist—and that they’re often no worse than the humans running the place.

A private eye in a city that never pretends to be clean

At the center of both novels is Jack Mitchell, a down-on-his-luck private investigator scraping by in an alternate version of Los Angeles not long after World War II. Jack fits comfortably into noir tradition: he’s cynical without being cruel, stubborn without being heroic, and perpetually short on cash. His city is filled with crooked cops, dangerous employers, and institutions that don’t protect people so much as grind them down.

What sets City of Shadows apart is that Jack’s Los Angeles doesn’t draw a bright line between the natural and the supernatural. Vampires have neighborhoods. Magic has rules and consequences. Ghosts, zombies, and other creatures exist not as shock reveals but as facts of life. Jack doesn’t gasp when he encounters them—he negotiates, adapts, and keeps moving, because that’s what survival looks like in this city.

Twice as Dead: noir cases with supernatural teeth

The first book, Twice as Dead, introduces both the world and its tone through a set of cases that initially resemble classic PI work. Jack is hired to investigate a missing person and to confirm suspicions of infidelity—standard noir entry points that gradually pull him deeper into a web of supernatural politics and personal danger.

One of the most important figures in the book is Dora Urban, a vampire whose role goes far beyond window dressing. Dora isn’t a love-interest cliché or a gothic ornament. She’s powerful, complicated, and dangerous in ways that feel consistent with the book’s noir sensibility. Her presence immediately signals that this series isn’t interested in romanticizing vampires or turning them into tragic symbols. They’re players—sometimes predators, sometimes victims, always political.

What makes Twice as Dead work is its refusal to treat the supernatural as an escape from noir’s bleakness. If anything, it intensifies it. The existence of vampires doesn’t make corruption more fantastical—it makes it more entrenched. Power structures adapt. Exploitation finds new forms. The city’s moral rot doesn’t disappear just because some of its citizens don’t breathe.

Lightning Runes: widening the circle of danger

The sequel, Lightning Runes, expands the scope without abandoning the street-level focus that grounds the series. Jack is again pulled into overlapping investigations involving organized crime, nightlife, and the entertainment world, all filtered through the same supernatural lens established in the first book.

The novel deepens its engagement with history, power, and responsibility, introducing antagonists whose monstrosity isn’t merely supernatural. Vampirism and lycanthropy coexist with very human atrocities, reminding readers that evil doesn’t originate with magic—it simply finds new tools. This is where Turtledove’s historical instincts quietly assert themselves. The supernatural elements don’t erase real-world horror; they underline it.

Just as importantly, Lightning Runes pushes harder on personal cost. Jack’s relationships—especially with Dora and others caught in his orbit—are strained by secrecy, loyalty, and the simple fact that survival often requires moral compromise. The book understands a core truth of noir: the longer you stay in the game, the harder it becomes to pretend you’re untouched by it.

Vampires without romance, monsters without mystery

For readers drawn to vampire fiction, City of Shadows offers something refreshingly unsentimental. These books are not about longing, immortality as metaphor, or forbidden romance. Vampires exist here as part of a social order, complete with hierarchies, prejudices, and vulnerabilities. They can be exploited. They can be hunted. They can also wield power in ways that mirror—and distort—human authority.

That approach aligns perfectly with noir’s worldview. In noir, systems are rigged, justice is conditional, and survival often requires making peace with ugliness. Adding vampires doesn’t soften that reality; it sharpens it. The monsters don’t replace human corruption—they participate in it.

The Los Angeles setting reinforces this idea. The city isn’t a backdrop; it’s an engine. Jazz clubs, backroom deals, racial tension, and postwar disillusionment all shape the world Jack navigates. Magic and the undead don’t overwrite those elements—they exist alongside them, making the city feel layered rather than gimmicky.

Why City of Shadows belongs on a vampire shelf

What ultimately makes Twice as Dead and Lightning Runes worth attention is how comfortably they inhabit both of their genres. They respect noir’s traditions—voice, atmosphere, moral ambiguity—while using vampires and magic as tools to explore power, identity, and survival rather than as genre decoration.

For fans of vampire fiction looking for something outside the usual lanes, City of Shadows offers a compelling alternative. These books aren’t asking you to fall in love with monsters. They’re asking you to watch them operate within a system that was already broken long before they arrived.

In that sense, Harry Turtledove’s vampire noir isn’t about hidden worlds at all. It’s about revealing what’s already there—just beneath the surface, waiting for someone stubborn enough to keep asking questions, even when the answers are dangerous.