More than a century after his arrival in the pages of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the Count has never stayed buried. He rises again and again, reinterpreted, reimagined, and rewritten for new readers and new eras. While Dracula has become a cinematic icon and a Halloween fixture, his roots are deeply literary—and it is in literature that the character has shown his most diverse, complex and enduring forms.

In this first installment of our four-part exploration of Count Dracula, we turn to the written word: from Stoker’s original epistolary horror classic to a sprawling multiverse of sequels, reinventions, novellas and graphic novels. The Dracula of the printed page is more than just a villain—he’s an archetype, a mirror and a shadow cast across literary history.

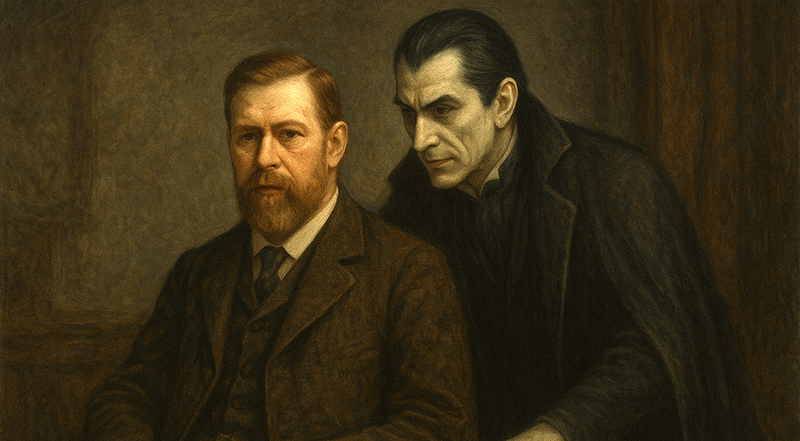

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897): The Original Undead

Published on May 26, 1897, Dracula was not the first vampire novel, but it became the most definitive. Drawing on earlier works like Carmilla (1872) and The Vampyre (1819), as well as Central European folklore and contemporary fears about immigration, sexuality and disease, Stoker crafted a complex narrative told through letters, diaries and news clippings.

The novel introduces Count Dracula as a powerful, ancient being from Transylvania who travels to England to spread his undead curse. He faces off against Jonathan Harker, Mina and Lucy, Dr. Seward, Quincey Morris, Arthur Holmwood and the enigmatic vampire hunter Professor Abraham Van Helsing. The group’s collective resistance frames Dracula not just as a supernatural being but as a colonial, corrupting force.

In her seminal study Dracula: Sense & Nonsense, scholar Elizabeth Miller wrote, “Dracula is a novel of anxieties—about gender, race, religion and modernity. The vampire is not simply a monster; he’s a threat to the status quo.” This duality—monster and metaphor—has defined Dracula’s literary life ever since.

Though the novel received modest reviews upon release, it gradually gained a cult following and by the 1920s was recognized as a cornerstone of Gothic horror.

Official and Unofficial Literary Sequels

Stoker died in 1912, but his creation lived on. Over the decades, authors, playwrights, and screenwriters expanded Dracula’s story—sometimes with the blessing of Stoker’s estate, often without.

Dracula’s Guest (1914) – Published posthumously, this short story was reportedly cut from the novel. It follows an unnamed Englishman (possibly Harker) who has a chilling encounter on the way to Castle Dracula. While not explicitly featuring the Count, it offers a tonal prologue to the novel’s events.

Powers of Darkness (1900/2017) – Originally a Swedish “translation” of Dracula, this text was later revealed to be a near-complete reimagining, introducing political conspiracies, new characters and more overtly fascist tones. Its rediscovery by scholar Hans Corneel de Roos reignited interest in how Dracula was reinterpreted across cultures.

Dracula the Un-Dead (2009) – Co-written by Dacre Stoker (Bram’s great-grandnephew) and Ian Holt, this “official” sequel is set in 1912 and reintroduces many of the original characters along with a now-tragic Dracula. The book divides fans but aims to expand the canon in line with Stoker’s notes.

Dracul (2018) – Also co-authored by Dacre Stoker and J.D. Barker, this prequel positions Bram himself as a character and explores the vampire lore of Ireland. Drawing from Stoker’s early notebooks, the novel merges biographical fiction with Gothic horror and received strong reviews.

Anno Dracula by Kim Newman (1992) – A metafictional alternate history in which Dracula marries Queen Victoria and rules Britain. The book is filled with characters from other vampire and horror stories, making it one of the most literary, referential Dracula pastiches ever written.

The Historian by Elizabeth Kostova (2005) – A modern literary thriller with academic characters chasing traces of Vlad the Impaler and Dracula across Europe. It became a bestseller and signaled the continued popularity of historical vampire fiction.

Dracula in the Short Story and Novella Form

Dracula has also appeared in dozens of short stories, both canonical and apocryphal. Anthologies such as The Dracula Book of Great Vampire Stories and Dracula in London (edited by P.N. Elrod) offer glimpses into the Count’s extended universe, often reframing him as either romantic antihero or unrepentant predator.

Notable examples include: “Dracula’s New Dress” by Tanith Lee, “The Night is Cold, the Stars Are Far Away” by Donald F. Glut, “My Mother, the Vampire” by Nancy Kilpatrick

These stories often reposition the vampire through different lenses: feminist, queer, postcolonial or deeply personal.

Dracula in Comic Books and Graphic Novels

If Bram Stoker made Dracula a literary legend, comic books gave him new visual power. Across publishers, decades and genres, Dracula has appeared as both monstrous villain and reluctant ally.

Marvel Comics’ The Tomb of Dracula (1972–1979) – Written by Marv Wolfman and drawn primarily by Gene Colan, this long-running horror title established Dracula as a complex antihero in the Marvel Universe. The series introduced characters like Blade and Rachel Van Helsing, blending superhero action with Gothic melodrama. “We wanted Dracula to have depth,” Wolfman told Syfy Wire. “Not just a monster, but a man who was once human, with regrets and rage.”

DC Comics’ Batman & Dracula: Red Rain (1991) – A dark Elseworlds tale in which Batman becomes a vampire to stop Dracula. The story, by Doug Moench and Kelley Jones, kicked off a grim trilogy exploring what happens when Gotham’s protector gives in to bloodlust.

Dynamite’s The Complete Dracula (2009) – A faithful adaptation of Stoker’s novel with elaborately Gothic illustrations by Colton Worley and text annotations by Leah Moore and John Reppion. Aimed at purists and completists.

Dracula: The Company of Monsters by Kurt Busiek (Boom! Studios) – A corporate horror story in which Dracula is resurrected as a tool of big business—and turns the tables.

Dracula, Motherfker!** (2020, Image Comics) – By Alex de Campi and Erica Henderson, this psychedelic reinvention brings Dracula to 1970s Los Angeles and reinvents his brides as his destroyers. Fast-paced, stylized and fiercely feminist.

Manga adaptations – Various Japanese editions and interpretations exist, including Dracula: Vlad Tepes by Osamu Tezuka and adaptations by Shinichiro Ishikawa, reimagining the Count through Eastern artistic traditions.

The Count in Modern Fiction and Mash-Ups

Dracula continues to appear across genres:

Dracula vs. Frankenstein, Dracula vs. Sherlock Holmes, Dracula vs. Hitler – Mash-ups abound, many unofficial, some satirical, others sincere.

Dracula in Love by Karen Essex (2010) – A feminist retelling from Mina’s point of view, exploring sensuality, repression, and identity.

Renfield: Slave of Dracula by Barbara Hambly (2006) – A compassionate novella that reframes the insane asylum inmate as a tragic figure.

Team-ups and battles – Dracula has battled everyone from Superman to Archie Andrews, appearing in Archie vs. Dracula and Superman #180.

Dracula as Literary Legacy

Dracula is more than just a character. He’s a trope, a metaphor and a literary mythos that continues to evolve. In his 2012 introduction to The New Annotated Dracula, scholar Leslie S. Klinger wrote: “Dracula is both a product of his time and beyond it. He represents sexual anxiety, colonial guilt and a fascination with the eternal. But above all, he endures because he changes.”

From aristocratic predator to tragic antihero, from horror villain to historical figure, the literary Dracula is a reflection of every era’s fears—and fantasies.