Before Dracula, before Carmilla, there was Lord Ruthven—the smooth-talking, soul-sucking aristocrat at the heart of The Vampyre, a short story written in 1819 by John Polidori. It’s often considered the first English-language vampire tale, and Ruthven set the mold for nearly every dark, brooding bloodsucker who followed.

The story begins in high society London, where Ruthven turns heads with his icy stare, mysterious past and a knack for ruining every woman who gets close to him. Into his orbit drifts Aubrey, a wide-eyed young gentleman who’s both fascinated and unsettled by this strange nobleman. The two head off on a European tour (as one does), but soon, things go off the rails. When a local girl is found dead—clearly the victim of something supernatural—Aubrey begins to suspect his traveling companion is more than he seems.

Eventually, Ruthven is mortally wounded, but before he dies, he makes Aubrey swear not to reveal what he’s seen… for exactly one year and one day. Naturally, Ruthven doesn’t stay dead. Aubrey returns to London only to find Ruthven alive, well and making moves on his sister. And since his oath isn’t up yet, there’s nothing he can do.

The clock runs out too late. Ruthven marries Aubrey’s sister, who is found dead the very next day. Ruthven vanishes. The end.

It’s a short, eerie tale that doesn’t tie up neatly—but it doesn’t need to. The Vampyre was a sensation when it came out and Ruthven became the blueprint for the suave, sinister vampire we still see today.

Character Snapshot

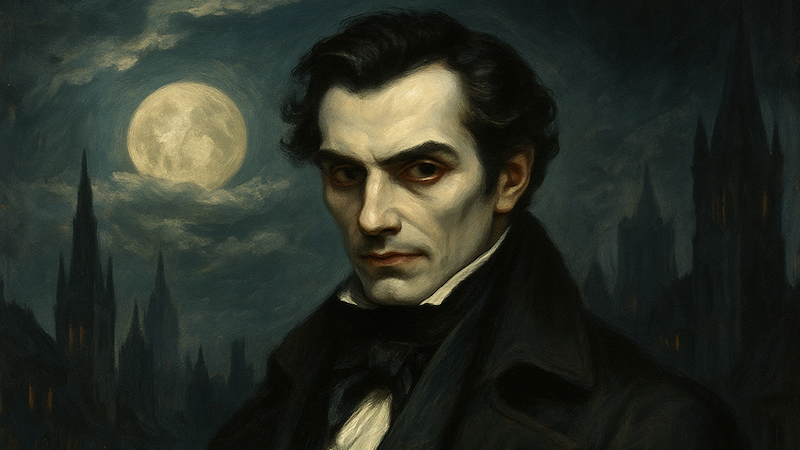

What makes Lord Ruthven so memorable? He’s not the snarling, monstrous type lurking in coffins—he’s the man sipping wine in your parlor, offering a half-smile while plotting your doom.

Cold, charming, and just a little bit dead behind the eyes, Ruthven is a walking contradiction. Women are drawn to him, men are unsettled by him and he always seems to leave devastation behind. He doesn’t bite necks in candlelit crypts—he destroys people slowly, from the inside out.

What’s even more interesting is how closely Ruthven resembles Lord Byron, the real-life literary rockstar Polidori worked for (and resented). When the story was first published, it was even mistakenly attributed to Byron, which caused a bit of a scandal. But intentional or not, the comparison stuck: Ruthven was the first vampire who felt like someone you might know—charming, magnetic, dangerous. The kind of person you regret trusting just a little too late.

In short, Ruthven doesn’t just kill. He ruins. And that made him one of the most fascinating—and enduring—monsters of early Gothic fiction.

Literary Origins

The story behind The Vampyre is almost as juicy as the vampire itself. It all goes back to the infamous summer of 1816—when the skies over Europe were darkened by volcanic ash, and a group of young, brilliant writers holed up at a villa on Lake Geneva. Among them: Lord Byron, Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley and a 20-year-old doctor named John Polidori.

To pass the time, Byron suggested they all write ghost stories. That challenge gave birth to Frankenstein (thanks to Mary Shelley) and, a bit more awkwardly, to The Vampyre. Polidori had been working as Byron’s physician and travel companion, though the two had a rocky relationship. Byron had scribbled the start of a vampire tale and abandoned it. Polidori picked up the idea, reworked it and created Lord Ruthven—who just happened to look and act a whole lot like Byron.

When The Vampyre was published in 1819, it caused a stir—not only because it was creepy and compelling, but because it was mistakenly credited to Byron. That mix-up added scandal to sensation, but readers devoured the tale of this fashionable bloodsucker who moved among the elite and left corpses in his wake.

Polidori’s Ruthven was a new kind of vampire: not a creepy peasant from folklore, but a refined, seductive predator. He didn’t live in a crumbling castle—he walked among high society. And that twist would influence every major vampire character who came afterward. So yes, Bram Stoker’s Dracula gets a lot of credit (and rightly so), but Lord Ruthven was the one who really opened the crypt for all the fanged aristocrats to come.

Adaptations and Appearances

Lord Ruthven may not be a household name like Dracula or Lestat, but he’s made some fascinating appearances over the last two centuries—especially if you know where to look.

Just a few years after The Vampyre was published, Ruthven was already taking to the stage. One of the first and most successful adaptations was the 1820 French play Le Vampire, written by Charles Nodier. It was so popular it inspired a trend called “vampire melodrama,” with Ruthven showing up in various disguises across European theaters. In these early versions, he wasn’t just undead—he was romantic, tragic and sometimes even sympathetic.

He also made the leap to opera, most notably in Der Vampyr (1828) by Heinrich Marschner, where he stalks the stage in full Gothic grandeur. Again, Ruthven was ahead of his time—charming audiences in velvet capes long before vampires became sexy in pop culture.

Fast forward to the 20th and 21st centuries, and Ruthven becomes a deep-cut favorite in horror literature and comics. He turns up in Kim Newman’s Anno Dracula novels as one of several scheming immortals. In role-playing games like Vampire: The Masquerade, he’s often nodded to as one of the “old ones.” He even got his own short-lived comic book appearances, including Marvel’s Vampire Tales.

Ruthven also continues to appear in TV and fiction as a kind of vampire hipster reference—someone creators pull out when they want to say, “I know my bloodsuckers.” He’s the vampire that predates Dracula, Carmilla, Varney—you name it—and in that way, he’s like the original vinyl collector in a world of Spotify vampires.

He’s never had the blockbuster treatment, but maybe that’s what makes Ruthven cool. He’s the deep lore vampire. The one who was haunting drawing rooms while other monsters were still climbing out of graves.

Legacy and Influence

You could argue that without Lord Ruthven, there is no Dracula. Or Carmilla. Or Edward Cullen. Or anyone else who ever made fangs fashionable. Ruthven didn’t just kick off the vampire genre in English literature—he redefined what a vampire was.

Before him, vampires were creepy old peasants from Eastern European folklore—figures of superstition, disease, and shadowy terror. But Ruthven? He strolled into high society wearing expensive clothes, flashing a cold smile and casually destroying lives over champagne. He introduced the world to the idea of the vampire as a gentleman, the predator hiding in plain sight.

That simple, brilliant twist is what stuck. Bram Stoker’s Dracula would take it further—adding old-world menace and blood-soaked grandeur—but the bones of the character are all Ruthven: immortal, manipulative, seductive, and often one step ahead.

Ruthven also carved out the idea that vampires don’t have to lurk in dark corners—they can live (or un-live) among us. He gave the vampire myth teeth in the drawing room, not just the crypt. And in doing so, he set the stage for every undead icon who would follow, from Anne Rice’s Lestat to Buffy’s Angel to the aristocratic monsters of What We Do in the Shadows.

Even today, if you scratch the surface of any dashing, dangerous vampire, there’s a little bit of Lord Ruthven underneath.

Quotable Reflections

For such a short story, The Vampyre has inspired a remarkable amount of commentary over the years—especially from those fascinated by its dark charisma and literary bloodline.

“The Vampyre was the first story to successfully fuse the old legends of bloodsucking corpses with the new anxieties of civilized society.”

— Christopher Frayling, Vampyres: Lord Byron to Count Dracula

“Polidori’s Lord Ruthven stalks the upper crust of society with cold detachment—less a monster, more a metaphor with fangs.”

— Nina Auerbach, Our Vampires, Ourselves

“Ruthven is Byron in everything but name—moody, magnetic, irresistible, and ruinous.”

— David Pirie, critic and Gothic historian

Even Polidori himself, in a 1819 letter to a friend, seemed both amused and agitated by the reaction: “I am not ashamed to own that The Vampyre, which has so long been attributed to Lord Byron, is mine.”

And from the original story, one of Ruthven’s most haunting moments:

“Upon entering, he smiled with that same cold smile, so frequent upon his countenance.”

— The Vampyre (1819)